The Master’s in Environmental Education program (MAEE) at Merry Lea Environmental Learning Center of Goshen College welcomed its largest cohort ever in July 2018.

The Master’s in Environmental Education program (MAEE) at Merry Lea Environmental Learning Center of Goshen College welcomed its largest cohort ever in July 2018.

The eleven students have filled every available rental space on Merry Lea’s property and triggered the purchase of a 15-passenger mini-bus. Counting students, summer researchers, interns and staff, a typical July day finds over forty people somewhere on the property.

From night hikes to The Crocodile Hunter

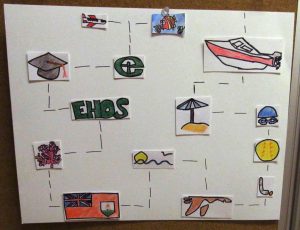

In the MAEE’s pedagogy course, students introduced themselves by way of a path map that described the experiences, mentors and decisions that brought them to Merry Lea. Any parents listening in could have picked up pointers on how to instill a love of nature in their children.

In the MAEE’s pedagogy course, students introduced themselves by way of a path map that described the experiences, mentors and decisions that brought them to Merry Lea. Any parents listening in could have picked up pointers on how to instill a love of nature in their children.

Formative experiences ranged from taking a night hike in the Smoky Mountains to watching The Crocodile Hunter on TV to a childhood fascination with an inchworm. Some students were taken to zoos as children; others went on family camping trips. One family owned a boat and spent many hours at beaches. The football coach, the neighbor with the taxidermy, the parakeet, the family woodland each triggered a love of nature in at least one MAEE student.

Adult ah-ha moments

The cohort mentioned “ah-ha moments” they had as adults as well. Terri Habig, Fort Wayne, Ind., remembers realizing that it was not only family—it was nature—that called her home to her roots after a long work week in a city.

The cohort mentioned “ah-ha moments” they had as adults as well. Terri Habig, Fort Wayne, Ind., remembers realizing that it was not only family—it was nature—that called her home to her roots after a long work week in a city.

Sam Buchanan, Madison, Ind., lived in Germany and was impressed by the way the culture reinforced practices like recycling with both carrots and sticks. It was convenient to recycle, and those who didn’t faced heavy fines. The German Green Party also intrigued her.

TJ Rayhill, Mount Washington, Ky., described a college course on environmental ethics that flipped his attitude. He’d grown up thinking environmentalism was a dirty word, but left the course viewing it as a Christian mandate. Two other students credited their Catholic colleges with instilling a sense of environmental stewardship.

One way that Emily Hayne, Mahtomedi, MN, learned respect for the land was through connections with the Anishinabe and Ojibway in her region. “Trees aren’t just resources; they’re relatives,” they would say.

Sarah Gothe, LaPorte, Ind., witnessed painful environmental destruction. She spent months on the Appalachian Trail processing the deforestation she encountered during a Peace Corps term in Madagascar.

Hopes for the future

The eleven students are not all seeking the same future. Dave Ostergren, the director of the MAEE program, notes that many people assume an environmental education degree focuses solely on leading hikes for children. MAEE students do teach in Merry Lea’s school programs, but the field of environmental education is much broader than that.

Vicky Benko, Lakewood, Ohio, and Joshua Crawford, Brighton, Mich., are two of the students who reported on the energy they derive from sharing nature with children. Delanie Bruce, Snyder, Neb., who spent a semester in Perth, Australia, dreams of being an eco-tourism guide abroad. Ali Sanders, Dover, Del., hopes to find work that allows her to travel while safeguarding marine life.

TJ Rayhill aspires to leadership—either as the director of a nature center or through work on environmental policy. James Austin, Foxboro, Mass., would like to be a naturalist with the Nature Conservancy or a natural history museum. Andrew Beal, Liberty, Ky., is interested in plants.

Some students are likely training for careers that don’t exist yet. “I think there should be land fill-ologists… [L]andfills are very rich in the human experience and they’re going to be a huge resource for the future,” Sarah Gothe concluded. Finding the value in landfills is part of “the integrated whole for future generations” that she hopes to help create.