Educators Celebrate an Amazing Year of Outdoor Learning

On May 9, Merry Lea’s Environmental Education Outreach (EEO) team wrapped up its first year of Kinderforest in a long-awaited burst of greenness. For a full day every month, two classes of kindergartners from Wolf Lake Elementary School, Wolf Lake, Ind., traded desks and bulletin boards for tree trunks and the crunch of leaves underfoot.

On May 9, Merry Lea’s Environmental Education Outreach (EEO) team wrapped up its first year of Kinderforest in a long-awaited burst of greenness. For a full day every month, two classes of kindergartners from Wolf Lake Elementary School, Wolf Lake, Ind., traded desks and bulletin boards for tree trunks and the crunch of leaves underfoot.

The children were part of an innovative model of education that is common in Europe but only beginning to take off in the United States. According to a 2017 survey, only about 250 nature-based preschools and forest kindergartens serve 10,000 children across the United States. Fewer than five are located in Indiana.

Children love it

As the EEO Team and Wolf Lake teachers looked back over the year, they found much to celebrate. They were pleased with the reciprocal relationship that developed between Wolf Lake teachers and Merry Lea and encouraged by the amount of interest other schools displayed in the program. First and foremost, however, Kinderforest worked for the children.

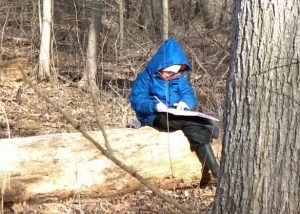

The Kinderforest day begins with time at a “sit spot.” Each child returns to the spot they chose at the beginning of the year to observe changes in the world around them and to write about what they see. Coming upon the group during this time is like encountering a band of small monks. The woods is silent and the children pay no attention to approaching guests. They are busy looking and listening.

The Kinderforest day begins with time at a “sit spot.” Each child returns to the spot they chose at the beginning of the year to observe changes in the world around them and to write about what they see. Coming upon the group during this time is like encountering a band of small monks. The woods is silent and the children pay no attention to approaching guests. They are busy looking and listening.

A generous amount of free play follows. This block of time looks like what people over fifty might think of as an ordinary childhood: children roam where they please, climb on logs and make things out of leaves and sticks. But today, in the era of state educational standards, computer screens and organized sports, such experiences are a luxury.

After lunch, which is eaten outdoors in Merry Lea’s council house, teachers present an activity related to that week’s classroom learning. Children might be challenged to find shapes, colors or letters in the woods around them. A counting exercise involved stringing leaves on a stick. April’s assignment was to make a nest out of materials found in the woods.

After lunch, which is eaten outdoors in Merry Lea’s council house, teachers present an activity related to that week’s classroom learning. Children might be challenged to find shapes, colors or letters in the woods around them. A counting exercise involved stringing leaves on a stick. April’s assignment was to make a nest out of materials found in the woods.

What did the children learn over the course of the year? Natalie Roberts, a student in Merry Lea’s master’s in environmental education program, focused on the students’ Kinderforest experience for her yearlong research project.

Natalie’s front-row seat as an observer enabled her to recognize the learning taking place during an activity like walking along a log with a friend. The process requires physical coordination, self-confidence and problem solving. As children taught each other how to navigate tricky spots and adjust their speed when the log was wet, Natalie witnessed increases in emotional development, social skills and self-efficacy.

“Things that seem really simple often have a lot of learning going on,” Natalie says.

It was clear that the children’s observational skills increased over time. Their ability to stay focused at their sit spots went from less than five minutes to fifteen. Independent of adult prompting, the children shared observations with each other. Natalie noted that the hike out to the trail shelters slowed down over the course of the year because the children kept stopping and showing each other things they had found.

Natalie also found that the children’s imaginative play became longer and more detailed. A downed log became a train and the leaves were the boarding tickets. Trees became places to play house. Advances in cognitive development, social skills and use of language made this possible.

Teachers Notice Many Benefits

As the Kinderforest year drew to a close, Wolf Lake kindergarten teachers Nancy Duffy and Jodie Jordan were emphatic in their praise for the program. At the beginning of the year, they assumed that science education would be the main benefit of Kinderforest, but as time went by, they were surprised by the breadth of learning that took place in the woods and the number of state standards they hit without really trying.

As the Kinderforest year drew to a close, Wolf Lake kindergarten teachers Nancy Duffy and Jodie Jordan were emphatic in their praise for the program. At the beginning of the year, they assumed that science education would be the main benefit of Kinderforest, but as time went by, they were surprised by the breadth of learning that took place in the woods and the number of state standards they hit without really trying.

According to Nancy, the sit spot exercise led to better writing in the classroom. When children were given a free writing period, they often chose to write about their Kinderforest experiences. When a child was having trouble finding a topic, a friend might prompt her with an idea from a shared experience during Kinderforest.

“It’s a real world reason to write, and when they have a real reason to write, they write better, and they write longer,” she said.

Jodie reported on the children’s enhanced sensitivity toward nature compared to what it had been at the beginning of the year. They were aware of grasses coming up on the playground and upset when a nearby tree was cut down.

Jodie was also pleased with the way Kinderforest benefitted many different types of students: those with high energy that found the classroom confining and those with less confidence. She also saw the gap between academically struggling and gifted students diminish due to the shared outdoor experience.

“I have never in my teaching career had children who were so supportive of each other,” Nancy remarked, as she described the social development she attributed to the Kinderforest experience.

“They talk out a problem. No matter if they are high ability or low ability children, they give one another a chance to talk. It is beautiful,” she added.

Community Interest

Educators outside of Wolf Lake Elementary School and Merry Lea are watching the program with interest. Over twenty teachers and administrators from other schools attended a Kinderforest Showcase that Merry Lea held March 21. The group was introduced to the educational philosophy behind Kinderforest and observed the outdoor classroom in action.

Educators outside of Wolf Lake Elementary School and Merry Lea are watching the program with interest. Over twenty teachers and administrators from other schools attended a Kinderforest Showcase that Merry Lea held March 21. The group was introduced to the educational philosophy behind Kinderforest and observed the outdoor classroom in action.

During the showcase, Marcos Stoltzfus, director of the Environmental Education Outreach Team emphasized the importance of the reciprocal relationship that developed between Merry Lea educators and their nearest school. The initiative came from Wolf Lake Principal Robby Morgan who realized how he might capitalize on the environmental resources available in his community. What emerged was a partnership, not merely a service Merry Lea provided.

“We’re willing to work with you to see how Kinderforest might work in your context,” Marcos told the group. Since then, he has been exploring possibilities with several schools.

Troy Gaff, superintendent of the Central Noble School District attended the showcase. He is supportive of the Kinderforest approach at Wolf Lake. “Even as an outdoor guy, I was hesitant because it was removing children from classroom learning. But once I saw it working, it was a no-brainer,” he said. He has fielded requests from the community asking that the program continue into higher grade levels.

Joe Pounds, director of adolescent well-being at the Dekko Foundation, Kendallville, Ind., also visited the Kinderforest program during the showcase. He was interested because the foundation supports healthy child development in the region. His interest was also based on personal experience:

“I remember very little about my third grade experiences. What I do remember mostly involves discipline. But fifty years ago in third grade, we were brought to Merry Lea. I was here at a sit spot writing a haiku. I remember the light that day, and I remember the spider I was writing about,” Joe recalls.

On April 6, Merry Lea received a $5,000 grant from the Dekko Foundation for its Kinderforest program. Ω